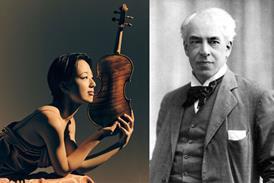

Exploring the parallels between theatre and classical music, violinist SongHa Choi shares how Stanislavski’s influential method acting books transformed her approach to performing Bartók’s Violin Sonata No.1

Discover more Featured Stories like this in The Strad Playing Hub

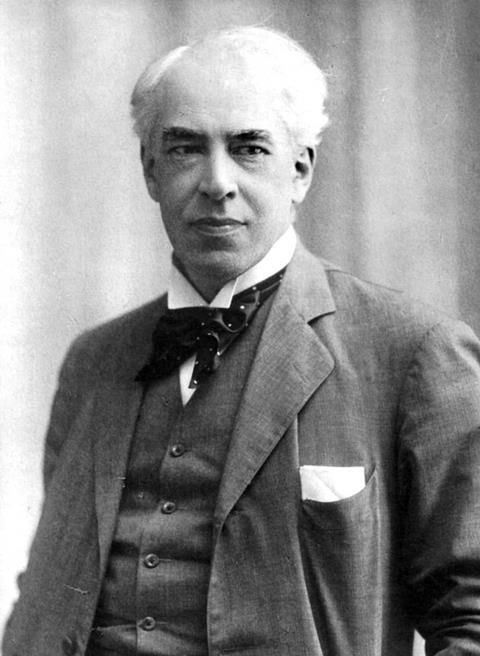

Actors and musicians share a common challenge in performance, that is, to make someone else’s words or notes feel as if they are happening for the first time. When I began preparing Bartók’s Sonata No.1 for violin and piano, I found myself borrowing ideas from the Russian director Konstantin Stanislavski’s method acting system. It was not out of theory, but out of curiosity and a desire for inspiration.

At the age of six, my first stage experience was not as a violinist, but as a child actor in a musical production in Korea. The role had been passed down to me through generations of actors before, and as rehearsals began I quickly realised that what I had observed in earlier performances would not be enough. I needed to make the lines believable, to bring them alive in the moment rather than to simply repeat them. That early experience left me with the sense that performance in any form is never only about external gestures, but about making even the smallest word or action carry meaning.

As I began to work on the Bartók’s First Sonata a few years ago, I returned instinctively to those theatrical ways of thinking. The piece is filled with harmonic complexity, sonorous melodies, and folk inflections that are deeply layered within the texture. They surface only rarely and never reveal themselves outright.

Personally, it felt like stepping into a script written with hidden cues and shifting subtexts. Stanislavski’s method acting system, with its emphasis on given circumstances, emotional memory, and the pursuit of inner conviction, became an unexpected yet natural guide. His trilogy (An Actor Prepares, Building a Character, and Creating a Role) may have been written for actors in the theatre, but the principles extend far beyond the stage for all art forms.

Stanislavski taught that nothing on stage is accidental. Every object, gesture, or pause has a reason to be there. Applying this to Bartók’s sonata, I began to ask why each interval, rhythm, or chord change existed, and tried to think from the composer’s point of view. Bartók was also a devout ethnomusicologist, dedicating himself to recording and studying folk traditions. To familiarise myself with that sound world, I listened to many of his archival recordings, folk instruments, as well as spoken audio texts in Hungarian to absorb the natural rhythmic accent of a language foreign to me.

Much of this work would never be visible to the audience, yet it helped me shape the atmosphere and character of the piece. I also began sketching emotional maps across the movements, tracing where I wanted the music to unsettle, evoke nostalgia, create distance, or spark excitement for the audience. The process shifted my focus away from technical polish and toward constructing a living world, where context and atmosphere mattered as much as the notes themselves.

Stanislavski taught that nothing on stage is accidental. Every object, gesture, or pause has a reason to be there

Stanislavski also emphasised the importance of narrative and role, and this led me to experiment with imagining the three movements through different perspectives. The first movement became a first-person voice: a direct, almost pleading melodic line that felt to me like the gesture of an elderly narrator slipping between past and present. The second unfolded in a third-person narration, as though describing a landscape from a distance, with temple-like stillness, insects buzzing, and frogs croaking animating the nature scene.

The third movement, by contrast, became a setting of rustic folk dance, with shifting perspectives between individuals and the collective, full of spirited dialogue in the style of the Hungarian verbunkos. Of course the scenes and characters continually change, but this way of assigning narratives helped me find a frame in which the music could speak more vividly.

Silence also carried its own role. Stanislavski often reminded actors that stillness can be as charged as speech, and Bartók’s sonata reminded me of this again. In the second movement especially, the long meditative lines required me not to be apologetic for the length of pauses but to allow them to exist fully, controlling their timing so that they became powerful elements of expression.

Stanislavski also believed in using memory and association as tools for emotional focus. I began experimenting with writing down single words in the score as emotional cues for myself, not to dictate a fixed programme but to help trigger an immediate response. Some of these cues worked better than others, but the act of trying them shifted the way I approach emotional planning. It was no longer only about repetition on stage, but more about cultivating responsiveness, a way of stepping immediately into the music as one might step into a role.

Theatrical method also insists that inner intention must come through in physical form. Bartók’s writing, with its particular attention to accent and articulation, demanded the same. For stringed instruments, we have the advantage of sustaining long lines without interruption, but this very continuity can also become a challenge: it risks ignoring the natural phrasing of a spoken or sung line. Thinking of the violin as a voice pushed me to consider breath and articulation in shaping melodies, especially in monologue-like passages and cadenzas.

I also experimented with ’bending’ intonation, in order to echo the unstable colours of folk instruments, as well as adding grain to the sound for texture or allowing certain notes to whisper. These gestures made the idea of this sonata less abstract, more like speech with its inflection and rhythm. And of course, no matter how much preparation one does alone, chamber music always demands openness. All of this work must remain flexible, because the first rehearsal will most definitely bring changes and new ideas, and every interpretation continues to evolve in dialogue with a partner.

In the end, the parallels between music and theatre became not a theory but a practice. Both ask performers to prepare with precision and personal imagination, and both only come alive in the presence of an audience. Stanislavski wrote that theatre exists only in the moment of its encounter, and music is the same. Preparation gives shape to the performance, but it is only in playing that it becomes itself, responsive to collaboration and to the listeners who complete it. Perhaps the real question for musicians is how we can carry the weight of that preparation into performance, yet still leave room for the music to surprise us?

Watch SongHa Choi’s performance of Bartók’s Sonata No.1, third movement, with pianist Yukako Morikawa.

Read: Postcard from Montreal: Montreal International Music Competition

Read: Becoming the fiddler: Fiddler on the Roof

Discover more Featured Stories like this in The Strad Playing Hub

No comments yet