Hector Scott explores sound, nature and the human search for purpose, from Mozart to Viktor Frankl

Read more Featured Stories like this in The Strad Playing Hub

The true importance of music does not lie primarily in its capacity to entertain, distract, or provide comfort, but in its unique ability to create a space in which human beings can explore meaning. Music invites both listener and performer into an active engagement with sound, where significance is not passively received but actively sought. In this sense, music functions as a form of existential inquiry, resonating deeply with Austrian psychiartrist Viktor Frankl’s conception of the human being as fundamentally oriented toward the search for meaning (Logotherapy).

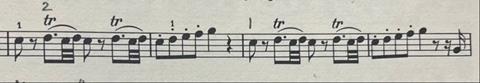

When a performer encounters a passage such as in Mozart’s violin sonata K.296 (Allegro vivace b.134) that resembles birdsong, the value of that moment extends beyond sensory pleasure. Meaning emerges through exploration in the struggle to produce the most aesthetically pleasing imagination of a bird singing. The listener attends closely, recognises an imitation of nature, and reflects on why such a gesture matters. In doing so, the listener and performer engage in a relationship with nature, with the composer, and with their own inner life.

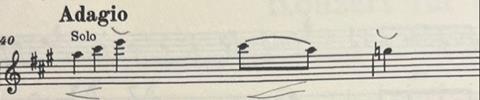

Another beautiful example of this is the opening solo of Mozart’s violin concerto in A. There is a silence before the soloist enters and the soloist enters without accompaniment, alone but not lonely. Unveiling a searching sound quality, it feels like an emerging sunrise that captures the miracle of birth. This relational process is central to Frankl’s philosophy, in which meaning is found through connection as in through love, through creative activity, and through encounters with the natural world.

Mozart and Bach embed this search for meaning within the very fabric of their music. Their works are not merely technical constructions or aesthetic ornaments, but carefully shaped explorations of order, imitation, tension, and release. Bach’s counterpoint reflects meaning generated through relationships. Independent voices which are listening, responding, and coexisting. Mozart’s music often draws the listener toward natural imagery, playfulness, and expressive clarity. In both cases, music becomes a means of exploring how human beings relate to one another and to the world beyond themselves.

Crucially, this exploration is never about achieving perfection. When a performer strives to imitate birdsong, they know in advance that perfect birdsong does not exist. Nature itself is fluid, unpredictable, and resistant to idealisation. Yet, it is precisely in the pursuit of this unattainable ideal that meaning is found. The value lies not in arriving at a flawless imitation but in the struggle or striving through attentive listening that integrates the performer with their tactile response to their instrument. Through the disciplined and creative shaping of sound, the ongoing dialogue between human intention and natural expression is realised. This aligns closely with Frankl’s belief that meaning is not located in outcomes but in orientation and in directing oneself toward something beyond the self.

Frankl’s reflections on life in the concentration camps further illuminate this perspective. He argued that survival and psychological resilience were deeply connected to whether individuals could locate meaning even under extreme suffering where material conditions were stripped to the bare minimum. Those who retained a sense of purpose, whether through relationships, memories of loved ones, or commitments to future goals, were better able to endure. Meaning, in Frankl’s account, arose not from comfort or success but from maintaining a relationship with something valued beyond immediate circumstances.

In contrast, modern society is defined by unprecedented material abundance. Central heating, hot showers, plentiful food, and constant entertainment are widely available. Luxuries that Mozart could scarcely have imagined. Yet, this abundance has not produced greater fulfilment. On the contrary, contemporary societies experience rising levels of depression, anxiety, and suicide. Frankl would interpret this as evidence of an existential vacuum, a condition in which comfort replaces but cannot substitute for meaning. When life no longer demands striving toward something beyond ourselves, purpose begins to erode.

Mozart’s own life was marked by struggle and uncertainty. He lived without many of the comforts that define modern existence, but he lived in close engagement with sound, nature, and aesthetic form. For him, music was not a consumable product but a way of relating to the world. The imitation of birdsong, the shaping of lyrical lines, and the exploration of expressive contrast and harmony were not attempts to master nature but to commune with it. Aesthetic engagement filled his life with purpose precisely because it required effort, attention, and humility in the face of something greater than the self.

For today’s musical performer, this pursuit remains central. Performance is not simply the execution of correct notes, nor is it primarily about pleasing an audience. It is an act of relationship-building with nature, with other musicians, with composers across history, and with listeners in the present moment. To strive toward the ‘perfect’ birdsong, while knowing it can never be achieved, is to accept a life oriented toward meaning rather than completion. Fulfilment arises from commitment to the process not from the illusion of final arrival.

Performance is an act of relationship-building with nature, with other musicians, with composers across history, and with listeners in the present moment

Modern music education, however, often neglects this dimension. When music is framed primarily as entertainment, classroom practice tends to prioritise familiarity and immediate enjoyment. Popular repertoire may engage students, but it rarely invites them into deeper exploration of sound as a source of meaning. This approach mirrors a broader cultural tendency toward consumption rather than connection. Students learn to reproduce what is recognisable rather than to listen deeply, imitate nature, or explore expressive relationships.

A more meaningful approach to music education would re-centre exploration and striving. Students would be encouraged to imitate natural sounds, to shape phrases as if responding to another voice, and to ask what music expresses about human and natural relationships. In doing so, music becomes not a distraction but a discipline of attention. It becomes a training in how to live meaningfully in relation to the world.

Ultimately, music matters because it addresses a fundamental human need. As Frankl argued, human beings are sustained not by pleasure or comfort, but by purpose. Music offers a unique pathway toward this purpose by inviting us into an endless pursuit of connection with nature, with others, and with meanings that can never be fully possessed. It is in this striving, rather than in perfection, that a fulfilling life is found.

Read: Challenge your curiosity and your preconceptions: violinist Hector Scott

Read: Breaking the sounds of sameness: why music education must resist global uniformity

Read more Featured Stories like this in The Strad Playing Hub

No comments yet