Read more Featured Stories like this in The Strad Playing Hub

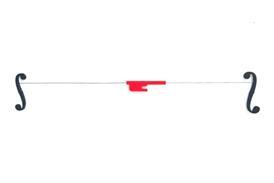

Paganini would allegedly break strings purposefully for showmanship, sometimes concluding a concert with a piece performed on a single string. Paganini’s bravura variations on a theme from Rossini’s opera, Mosè in Egitto, directly connect to the vocal ideas of the fashionable Italian opera that so influenced his work.

In this piece, Paganini borrows the famous aria, ’Dal tuo stellato soglio’ (’From thy starry throne’), which was immensely popular at the time and represents the prayer of Moses and the Israelites at the banks of the Red Sea during the Exodus from Egypt. Paganini masterfully imitates the different registers of Rossini’s dramatic aria and follows it with a set of virtuosic character variations performed entirely on the G string. Composed in 1818/19 for violin and orchestra, the work was originally conceived for scordatura, with the G string tuned up to B-flat.

In ’Mosè,’ the noble, slightly melancholic melody in a minor key is heard in different registers, then returns in the major key. A brief cadenza leads into an elegant march-like transformation of the theme, followed by three increasingly intense and virtuosic variations on ‘Air de Ballet’ from Abbe Volger’s Castore e Polluce, culminating in a fast-paced finale.

Music was at the forefront of Paganini’s enchantment, as judged by many esteemed composers including Rossini, Donizetti, Schubert, Chopin, Schumann, Liszt, Verdi, Brahms, and Bellini. Numerous compositions by his contemporaries incorporate and draw from his works, and reverence for Paganini’s musicality is illustrated by quotes from Schubert: ’I have heard an angel sing in the Adagio,’ and Rossini, tongue-in-cheek, who said: ’I have wept only three times in my life… The first when my earliest opera failed, the second when, on a boating party, a truffled turkey fell into the water, and the third when I heard Paganini play.’

For my recording, I used standard tuning and Zino Francescatti’s edition for violin and piano. Interestingly, Francescatti’s pedagogical lineage traces back to Paganini through his mother, Ernesta Feraud, a student of Fortunata, who was a student of Camillo Sivori, one of Paganini’s two successful students.

Using standard tuning is convenient for players with perfect pitch and also enhances resonance through the sympathetic vibration of the open strings. Keys like G major benefit especially from this effect, as their harmonic content aligns with the open strings.

Shortly before the recording, I decided to use a strong gauge G string to replicate the higher tension of scordatura. This increased tension contributes to the brilliance and power associated with scordatura, as tightening strings focuses the violin’s sound and improves projection. This approach may not be universally recommended, however, as strong gauge strings require more bow pressure and may be less responsive, particularly for quick passages and left-hand agility.

The G string presents unique challenges in terms of response. Being thicker, it requires more bow pressure and slower bow speed, similar to a double bass, which uses shorter strokes and stickier rosin. The challenge is to get a crisp and clear sound even in high positions where the vibrating portion of the string is short. ’Mosè’ offers a rare chance to explore what it takes to make the G string respond across a wide expressive range, from lyrical bel canto lines to fast, articulated passages. For the latter, using very little bow with a strong grip is effective.

In the finale, fast spiccato often emerges naturally from the bow’s friction, but under a slur, it is sometimes necessary to rearticulate so subsequent notes speak clearly. Overly fast tempos can cause the G string to lag, sometimes it simply needs more time to respond.

Paganini offers a way to explore and deeply reconsider the efficiency and intricacies of our own playing. Shifting is an essential part of ’Mosè Fantasia,’ and the piece provides a great opportunity for students to dive into technical challenges embedded in real music, rather than only through studies like Ševčík Op. 8. The difficulty lies in executing precise shifts on the lowest and farthest string, the G string. The key is to find a fluid, efficient way to move up and down the fingerboard by freeing the elbow and establishing a smooth path that avoids bumping into the body of the violin.

A useful exercise is to place all four fingers very lightly on the string and slide rapidly up and down the fingerboard using a forearm motion. This develops awareness of the bold arm movement and inner elbow position needed for fluid shifting. It is important not to press with the left-hand fingers during the shift.

A principle I often emphasise is ’left before right,’ ensuring the left-hand lands and secures the pitch before the bow engages. Many students rush unconsciously, not allowing for the time complex passages require. Once students create that space, often through quiet mental anticipation, both accuracy and ease follow. I encourage thinking of shifts not as instantaneous teleportation but more like an elevator: starting slowly, traveling smoothly, and arriving with control. I also use the image of ice skating: a continuous glide rather than a jerky motion. In lyrical lines, glissandi are musically appropriate.

A common challenge is getting the third and fourth fingers to sound in tune in higher positions. I recommend pivoting the hand toward the upper fingers in higher positions, letting the first and second hover or remain loose. I call this the ’teeter-totter’ approach as the hand angle pivots. It shapes a better left-hand frame, improves intonation, and reduces unnecessary tension.

In the theme of the piece, one should avoid throwing the bow on down-bows out of lack of control or to force a temperament, and refrain from creating unnecessary accents when recovering the bow quickly.

In cadenzas (Theme and Variation II), grouping notes musically by emphasising structurally important tones while lightly treating ornamental ones, as in a coloratura passage, enhances both musicality and technical dexterity.

When it comes to harmonics, maintaining a stable hold of the instrument between the clavicle and chin is important, though this should be done without pressing. The left thumb should remain free while keeping tactile awareness of the fingerboard. It is a delicate balance of stability and freedom. I move the thumb along with the hand in lower positions; in high positions, I prefer a middle position where the thumb remains stationary, and the fingers move flexibly around it.

Paganini reportedly used this approach often, he is believed to have had Marfan syndrome or a similar condition granting extraordinary joint flexibility, allowing large stretches from a single hand position. A good example is about nine bars before the end of the finale, where the left elbow and thumb remain stable while the fingers shift back and forth.

The right hand is just as crucial when producing harmonics. The string must speak clearly (not whistle), and one should avoid excessive bounce in the bow. If the bow hits the string too hard or high, even in spiccato, the response becomes inconsistent.

For the ponticello in Variation III, bow placement is critical. There’s a natural tendency for the bow to drift away from the bridge, as our ears instinctively avoid the edgier sound. The solution is to stay calm and keep the bow near the bridge, even when it feels counterintuitive.

Finally, intonation in high positions can be particularly challenging. I recommend adhering to the idea of vibrato as an effect rather than a continuous addition, as did Paganini (implied by an annotated version of the Caprices indicating specific places for vibrato). Also, keep the vibrato tight in high positions to avoid pitch variation.

Beyond technical control, the shortening of the vibrating string results in fewer overtones compared to higher strings. Sometimes it is necessary to depress the string fully to the fingerboard. One can also explore the angle of the fingertip (particularly the last knuckle) or bring the elbow further in, targeting the inside of the G string rather than the edge near the D string. These small adjustments, along with bow speed, contact point, and dynamic level, help clarify pitch and improve tone colour.

To me, Paganini’s music represents a musical language not unlike the human voice, one that is beautiful, moving, and full of character. Aside from his incredible showmanship, accounts of his performances refer to his lyricism, deep feeling, tonal variation, and communicative playing, in his words, ’suonare parlante’ (playing that speaks).

Paganini’s quote, ’In order to move others, I must be moved,’ is testament to the fact that emotional expression was as vital to Paganini as technical brilliance, an important sentiment to keep in mind when tackling the unique difficulties of performing his music.

Paganini’s Mosè Fantasy is featured on Tomas Cotik’s album Capriccio, released on 24 October 2025 on Centaur Records, which also includes Cantabile and a wide selection of solo Caprices.

Read: Piazzolla’s musical style by violinist Tomás Cotik

Read: Mastering up-bow and down-bow staccato

Read more Featured Stories like this in The Strad Playing Hub

No comments yet